I suppose a pregnant, serial killer, car-show stripper is as good a son as any.

Upon first impressions, Julia Ducournau’s 2021 film Titane appears to demand deep and even excessive analysis, its surrealism, absurdist qualities, and gender fluidity urging further reflection. And for good reason — it’s a brutal and singular clash of flesh and metal so wild and unhinged that it often fuels conversation and debate that trickles on without any clear resolution. But perhaps the shocking imagery – the human-on-car sex, the graphic brain surgery, the nipple piercing abuse, and the full-frontal oedipal longing – is Ducournau’s way of screaming a theme that is often delivered in a whisper. At its core, Titane is a story about a child who reshapes herself to be worthy of love, and a father who creates a fantasy in order to reclaim the love he once lost. Though saturated in a frenzied outer-layer, Titane has a soft heart. Ducournau, through layers of titanium and guts, explores a simple theme: the idea that everyone longs to love and be loved.

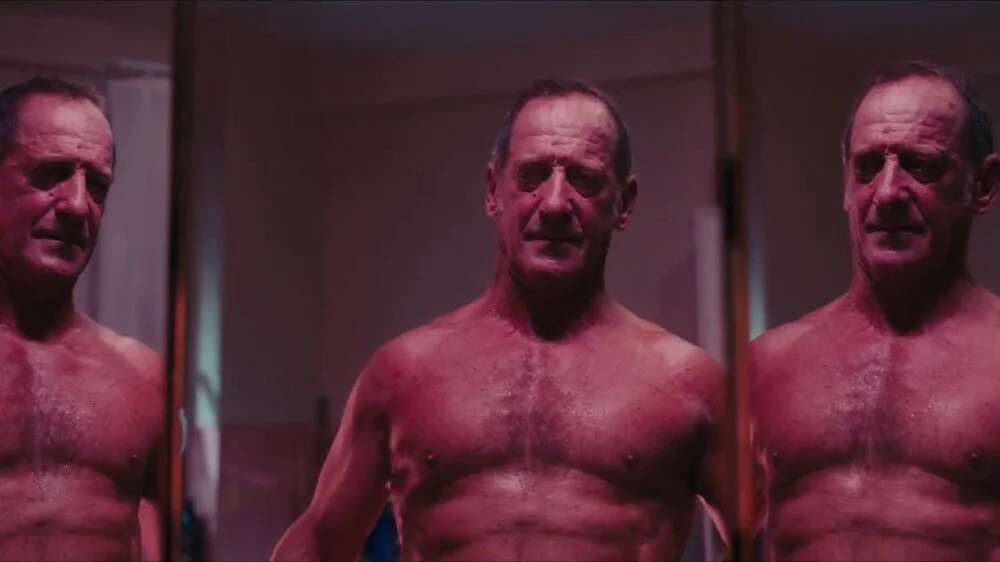

Similarly to Alexia, Ducournau has us watch as Vincent fights his own decay, injecting synthetic youth into his frail body – his veins pulsing, muscles tense. Ducournau externalizes both characters’ deteriorating, broken bodies as physical manifestations of their internal struggle for connection. Alexia and Vincent are nausea, they’re humiliation — they’re the personified shame of searching blindly for love. Ducournau bathes Vincent’s body in pink light that seems to strip away his skin, exposing him as a raw, pulsing mass of flesh. This synthetic glow mirrors the artificial youth he injects into himself through steroids, while simultaneously offering an unflinching exposure of the exact physical flaws he’s so desperate to conceal.

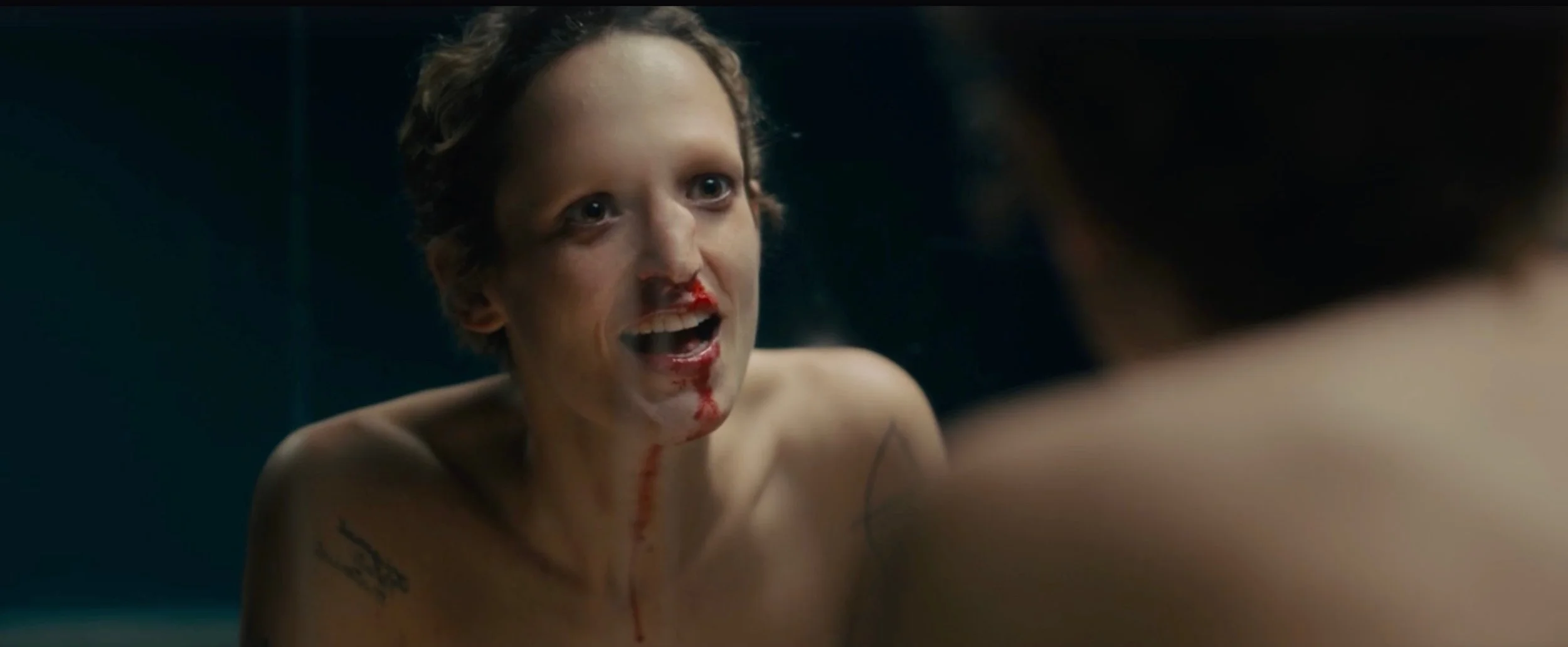

Alexia smiling in the mirror after successfully breaking her own nose

Titane centers around Alexia, who, after surviving a childhood car accident in which she received a titanium implant in her skull, goes on the run following a series of violent acts. In fear of being caught by authorities, Alexia assumes a new identity and is taken in by a grieving firefighter who believes she is his missing son, Adrien.

Ducournau uses body horror to engage with this idea of longing for love, battering the viewer with images of bodily transformation on the part of both Alexis and her new “Father,” Vincent. We watch as Alexia binds her chest with bandages, bashes her nose against a sink, leaks black oil from her breasts — up until her final moments where the agony of labor rips open her stomach.

Examples of Body Horror in Titane

Vincent, moments after injecting himself with steroids

Titane’s frenzied and explosive plot serves as a vessel for these two characters to find one another and to exhaust themselves nearly to death in the search for the one thing their lives lack — revealed through Ducournau’s poignant use of body horror.

In the film, Alexia smiles a total of five times. Three lack sincerity: once for a staged photo, once at the recovery of a weapon, and once with a short, hollow laugh when asked a question she has no intention of answering. But only two of these smiles feel real—one born of love, and one at the fragile hope of receiving it. The first true smile arrives around the 36-minute mark and quietly signals the emotional core of the film. After binding her breasts and pregnant stomach, hacking away at her bleached hair, and violently breaking her own nose in order to resemble Vincent’s missing child. Alexia looks into the mirror, face bloodied and bruised, and smiles. It is not a moment of triumph, but belief. It’s the fleeting, deluded sense that she has reshaped herself into someone worthy of love. She has contorted her body, erased her identity, and endured pain to finally become what she imagines will be acceptable. What follows is anything but simple, but in this moment, she believes she has succeeded.

The second smile comes an hour and twelve minutes in. Alexia and Vincent dance together beneath the soft, synthetic glow of pink light, surrounded by Vincent’s firehouse crew. “Light House” by Future Islands plays — a pulsing, emotional backdrop to the moment — and Vincent lifts Alexia, tossing her over his shoulder. The scene plays like a warped version of a father-daughter dance, filled with a sense of suspended disbelief and tenderness that leaves both characters recognizing the fruition of their efforts. It's quiet and strange, almost surreal, but ultimately sincere. This is not the smile of someone playing a part — it’s the genuine expression of someone who has, perhaps for the first time, felt truly seen and accepted. That same pink light that Ducournau uses to strip Vincent down to his flaws is used to strip past Vincent and Alexia’s facades they’ve built. On this makeshift dance floor, true, honest love is revealed.

To truly understand Titane is to strip back the chaos and surreal extremes and to instead focus on the love leaking through. Through the characters’ internal cries for love made visible on their flesh through Ducournau’s use of body horror, the film reveals a quiet, devastating truth: people will do anything, believe anything, to be loved, and to love in return.

Alexia and Vincent dancing to “Light House”