What Brokeback Mountain & Giovanni's Room Can Teach us About Shame

“What terrified me was that I had come to the city intent on finding this. What terrified me was that I had found it.” - Giovanni’s Room

Giovanni’s Room and Brokeback Mountain don’t extract pain from queer love itself, but rather, the deep anguish that comes from chasing love after it's been lost. In the respective works, shame emerges at the moment of desire, but ultimately sets up camp in the aftermath of love denied. This second shame, born of regret and longing, is heavier, more corrosive, and arguably more undignified than the initial fear of visibility. The tragic irony is that once these men cross into this second realm after rejecting love out of fear, the love they abandoned becomes pure, even sacred. But for our protagonists – David and Ennis – it’s too late.

James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room centers on David, an American in Paris, who falls into a passionate affair with Giovanni, a charismatic bartender at a smoky, parisian gay bar. David, fearful of the implications of their love, ultimately flees it, choosing a loveless heterosexual marriage with an American flame, Hella. To his surprise, it is not the act of loving Giovanni that ultimately torments David the most, it’s the haunting knowledge that he will never find anything like it again. Baldwin writes, “Nothing is more unbearable, once one has it, than freedom.” By abandoning Giovanni, David gains the freedom to live the “normal” life he thinks he should want—but ultimately falls prey to a greater shame than he knew possible.

David’s early shame — fear of being known, of being exposed, — is familiar. But it pales in comparison to the quieter, more consuming shame that follows: the shame of knowing he will spend the rest of his life trying to recreate the intimacy he had with Giovanni through more desperate, fragmented means. Baldwin foreshadows this descent with devastating clarity, writing, “The beast which Giovanni had awakened in me would never go to sleep again; but one day I would not be with Giovanni anymore. And would I then, like all the others, find myself turning and following all kinds of boys down God knows what dark avenues, into what dark places? With this fearful intimation there opened in me a hatred for Giovanni which was as powerful as my love and which was nourished by the same roots.”

Copies of Giovanni’s Room, James Baldwin’s 1956 novel

This idea cuts to the heart of Baldwin’s tragic thesis. David’s shame is not rooted solely in the act of being with Giovanni — it is rooted in the terrifying realization that he is now resigned to spend his days chasing the ghost of that love in increasingly shameful, hollow ways. He fears, even as he clings to Giovanni, that he will turn into one of those men he once judged, drifting through dark city streets in search of fleeting physical connection—desperate, and never satisfied. In that moment, the shame of desire becomes fused with a deeper shame: that he will never again experience love as full and as terrifyingly real as what he had with Giovanni. Amidst this realization, any shame he felt during the love affair pales, becoming almost noble in comparison. What follows is far worse: a life of disconnection, of impersonating desire without intimacy, of searching for pieces of Giovanni in men who only serve as dim reflections of what was lost.

What Baldwin reveals so powerfully is that David’s rejection of Giovanni isn’t just a rejection of love, it’s a rejection of the version of himself capable of love. As a result, David lives fractured, never able to return to the wholeness he once knew. His future can only hold a string of dishonest relationships, secretive encounters, and growing disillusionment. He chooses a kind of moral exile in which every source of pleasure is only a poor imitation of the love he threw away.

Brokeback Mountain follows a strikingly similar trajectory. Ennis Del Mar and Jack Twist fall into a fiery affair while herding sheep in the Wyoming mountains. Ennis, paralyzed by fear of discovery and the threat of violence, pushes Jack away repeatedly. He marries, raises children, and insists to himself that their summer was an anomaly. “If you can’t fix it, you gotta stand it,” he says, a declaration of resignation more than strength.

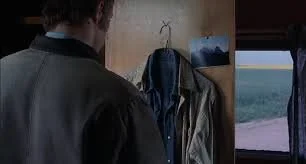

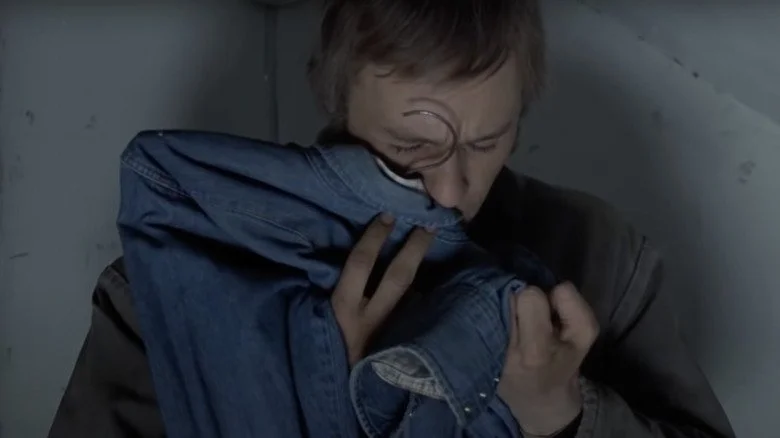

Ennis finds Jack’s Jacket following his murder (Brokeback Mountain)

Stills from Ang Lee’s 2005 film Brokeback Mountain

Jack, more willing to embrace the possibility of love, tries to reason with Ennis that its possible for them to build a life together. But Ennis, paralyzed by fear and internalized shame, continues to push him away until it’s too late. When Jack is murdered, Ennis is left not only to mourn his loss, but to confront the far deeper wound: the absence of the life and love he refused to claim. But the more enduring pain isn’t just Jack’s death, it’s the realization that everything Ennis will ever feel from now on will be a diluted version of what he once had and feared too much to keep. The memory of Jack becomes untouchable, a kind of sainted love in the absence of which Ennis is left to drift. His final moment with Jack’s shirt is not just grief; it’s self-condemnation.

Like David, Ennis is not destroyed by the act of love—but by his refusal to hold onto it. His life becomes a long stretch of emotional vacancy, his loneliness less about lack of opportunity and more about lack of will. He lives on, as David does, haunted by a love he didn’t think he could claim. And like David, the purity of the lost love only becomes clear once it’s out of reach. What was once frightening becomes holy—a love sanctified through its transformation from threatening to non threatening.

In both stories, the men’s initial fear of being outcast is real. But it is the loss of what they had, and their subsequent attempts to fill the void, that generate the deeper, longer-lasting shame. These are not simply stories of homophobia or repression. They are stories about what happens when love is made irretrievable by fear. In the wake of that loss, the original relationship takes on an almost mythic quality, and everything else becomes a poor imitation.

David and Ennis are not destroyed by love, they are destroyed by their refusal to fight for it. And what remains is not peace, but a lifetime of looking backward. In the novel’s final pages, David wanders alone, saying, “I cannot guess what I will do, but I will be doing it alone.” He does not find redemption. He finds only distance from the one moment in which he was fully alive. Similarly, Ennis, gazing at Jack’s shirt in their final scene, softly says, “Jack, I swear…” but it’s a vow made too late.

In Giovanni’s Room and Brokeback Mountain, the tragedy is not in loving another man, but in the vehement belief that shame resides in the act of love, not realizing that chasing its shadow — through deception, denial, or isolation — is the shame that never ends.

These stories transcend simple moralizing cautionary tales; they are profound explorations of the human condition. They reveal the devastating consequences of allowing fear to govern our ability to connect authentically. The prioritization of safety over truth makes way for temporary comfort, but costs us the very core of ourselves. In that profound loss, love transforms into something both sacred and painfully elusive. It mutates into something forever cherished in the safety of memory, yet forever beyond our grasp.